Given how poorly my 1960s John Stanley Bibliography has sold, I'm feeling rather discouraged about the hard work it will take to put together the 1950s volume. In the work I've done so far, if only to satisfy my own curiosity, I've made some pleasant discoveries and done some re-evaluations.

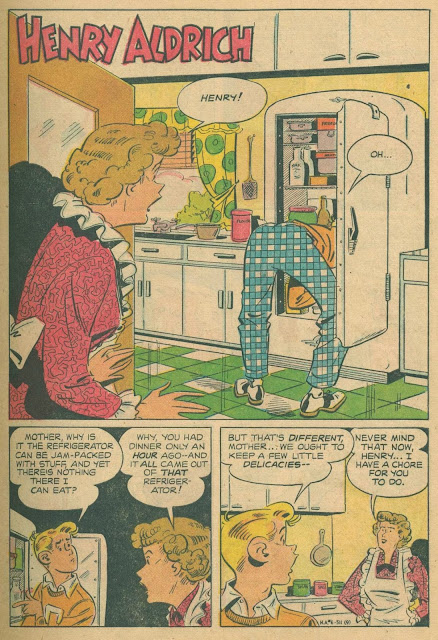

The richest vein I've struck is in the early 1950s title Henry Aldrich, which Stanley wrote for his most talented collaborator, the cartoonist Bill Williams.

As Stanley entered his most beloved period on the best-selling Marge's Little Lulu title, and just before he took up cartooning again for the eclectic Marge's Tubby spinoff, he wrote several issues of this teenage analog to Lulu and Tubby.

Stanley's Aldrich material is often surprisingly sophisticated, and the book's unusual format allowed him to experiment with story lengths. Today's offering is one of Stanley's longest regular-issue narratives: 31 pages of unfolding comedic mayhem, tinged with black humor and featuring two protagonists who never quite understand why their actions have such a strong effect on the world around them.

The untitled story's highly innocuous kitchen scene, at its start, doesn't reveal one iota of the manic escalation that hits Henry and his best bud, Homer, like the proverbial dresser-drawer-full-of-bricks...

A seasoned reader of John Stanley's Thirteen Going on Eighteen can find much to savor in this untitled story. Like the recently posted "Homer Brown" stories, this piece shows that Stanley's 1960s comedic style did not just spring out of the ether. The highly controlled world of "Little Lulu" didn't leave Stanley much breathing room. Events too wild, morbid or off-kilter wouldn't work in the "Lulu" arena.

This story was written before Stanley's remarkable series of book-length stories for the Marge's Tubby comic book. Though Stanley had written (and sometimes drawn) several longer narratives by 1950, when this story was created, he had seldom reached this level of sophistication. "Lulu Takes A Ride," from 1947, comes closest to achieving this story's sublime, patient and measured comedic escalation.

The story harkens back to two significant Stanley pieces from the New Funnies monthly anthology. This Andy Panda story from 1947 (buried within a longer, more general post) has a remarkably similar sequence in which the two protagonists attempt to return a stolen cannon by car.

This Woody Woodpecker story, also from '47, is built around assumptive misunderstanding of an innocent act that seems sinister. It, too, calls in the police, including... well, read the post and see for yourself.

Alert readers will notice the reference to Kohlkutz, the butcher--who also appears in many "Little Lulu" stories. Stanley was evidently very fond of this W. C. Fields-esque name.

Stanley had the opportunity to revisit narrative and comedic ideas time and again in the world of comic books. These mass-produced, disposable pamphlets, forgotten by most as soon as they reached their sell-by date, had a huge turnover in their readership. A good idea was most definitely worth repeating, or re-exploring.

Several such strains of a theme approached, retried, refined and perfected occur in John Stanley's work. This is one of the most spectacular realizations of a solid comedic idea in all of comics.

Stanley, at his best, keeps small, absurd ideas moving through the flow of his story. In this case, it's the boys' remembrance of a horrible fruit punch drink, made by Homer using cider vinegar. That incident keeps bobbing to the surface of the story, as Henry and Homer get enmeshed in a town-wide crisis that ends with a massive police stand-off, guns at the ready, in their own backyard:

This comedic apotheosis had no place in Little Lulu's world. It is the type of moment that modern licensed-property holders have in their worst, wake-up-screaming-and-sweaty nightmares. No corporate entity would allow their properties to be held at bay with riot guns! The freedom of neglect that Stanley, and other Western Publishing creators, enjoyed with their licensed charges, in the 1940s, '50s and '60s enabled them to make bold choices, and to introduce ideas that were far richer and more complex than the official version of Henry Aldrich, Woody Woodpecker, Howdy Doody, etc., etc.

Stanley was the only Western creator to take full advantage of this freedom, and this story is one of the richest fruits of such anonymous labor. That he also had 52 pages to fill any way he chose, with little editorial interference, allowed him to, at whim, write out a story to its natural length. This could have been a 10-page story, stripped to the essence of its plot. With 31 pages, Stanley and Williams can indulge themselves in non-essential but dazzling touches. Incidental characters who'd have no more than a "YOW" in a shorter story get to exchange significant dialogue (e..g, the napping department store employee with the mannequins; the spinster women who call the police near story's end).

The reward of this story is its leisure. It builds slowly and inexorably from a stock premise, invests it with character and stakes, and lets it come to a boil. Were Henry and Homer not so concerned about their social status, none of the events of this remarkable story would have taken place. Because their egos, and their misguided perceptions of the world, inform their thoughts and deeds, they take the hard way; their misfortune and growing confusion allows a level of character richness seldom seen in mid-20th-century comics.

John Stanley's Henry Aldrich stories are perhaps the best hidden gems of his prolific career. They are subtle, smart and understated in all the right places, and zany when zany is most needed. They're written with the same control as Stanley's concurrent "Little Lulu" stories, but they get to explore different places than most mainstream comics of their era.

1 comment:

This story feels 10 or 12 years more recent.

There was a Little Lulu story published that same year (1951) titled Five Little Babies were Lulu gets Tubby and his friends to wear diapers, they cover themselves with a burlap and pile up on a kid's wagon, the wagon rolls downhill and people think it's full of feet. It's a similar type of dark humor to Henry Aldrich's dummies being confused for mutilated corpses.

Post a Comment