As I've said before, this is not a "Little Lulu" blog. Aside from John Stanley's interpretation of the character, in his 14 years as writer-layout-cartoonist for the Dell Comics adaptation, Lulu rather leaves me cold.

The background story of the creation of Marjorie Buell's "Little Lulu" is far more interesting than her actual work. She is a poor cartoonist, and a poor gag-writer, in my opinion.

Despite the contemporary popularity of her magazine cartoons, time has not been kind to Buell's work. Her sheer lack of skill as a cartoonist and drafts-person gives the work a cheap, amateur-hour feeling. The character of Lulu never evolves beyond that of a one-dimensional prankster imp, whose misdeeds hide under a tin halo of childish innocence.

Little Lulu was created as a replacement for Carl Anderson's "Henry," which departed the

Saturday Evening Post in 1935 for a long run with King Features Syndicate. (Some poor soul still continues his mute, anus-faced adventures, which run, among other places, in the online Seattle

Post-Intelligencer.)

John Stanley worked a small miracle in his rethinking of the "Little Lulu" character and universe. He gave each character a highly developed, believable and rich personality. He also clearly defined their habitable world. The Northeastern landscape of his "Lulu" is, itself, a major character in the Dell series.

Marge Buell cared for nothing more than a quick laugh, dusted with a little bit of cloying charm. It was enough to delight the 1930s reading public. For the character to exist beyond the pantomime plane of the gag cartoon, Lulu needed substance in the worst way.

The first major adaptation of Buell's character precedes John Stanley's first

Little Lulu comic book by almost two years. She appeared in 26 animated cartoons, produced from 1943 to '47 by New York-based animation house Famous Studios. These cartoons clearly occupy a warm, nostalgic place in the hearts of many folks.

They compare and contrast with the greatest iteration of the Marge Buell characters--those done, in Dell comic books, by John Stanley, Irving Tripp, and others, from 1945 to 1959.

Those with starry-eyed fondness will not like much of my comments and reactions to the Famous Studios cartoons. Had Stanley not done the subsequent comic book version--the iteration of Lulu with which I'm most familiar and grounded--perhaps these cartoons would seem less strange and off-kilter to me.

That said, I am an admirer of the Famous Studios output. At its best, particularly in the time-period of the "Lulu" animated shorts, Famous offered a refreshing, often visually spectacular counterpart to the West Coast animation houses. They carried on a hint of the vibe of the original studio, headed by the Fleischer brothers (Max and Dave). Highly recommended is

a new DVD from Thunderbean Studios that contains ravishingly restored prints of 20 early Famous Noveltoon cartoons.

Many of these early Famous shorts fell into the public domain, and, until this DVD, have only been viewable in dreary, color-faded and corrupted TV prints. Seeing the cartoons via this DVD gives you a much clearer impression of how they looked when they were new--and what a curious, distinct flavor Famous' early output has to offer 21st century viewers.

The first few "Little Lulu" shorts were among the last cartoons produced at the studio's Miami, Florida outpost--the last bastion of the flagging Fleischer studio. Most of the screen "Lulu" cartoons were created in New York, near to where John Stanley wrote (and drew) his entirely different take on the Marge Buell character for Western Publications. Though Famous had a two-year head start on the Buell property, it is fascinating that, in the same general area, at the same general time, two different creative teams were at work on their interpretations of a popular pop-culture figure.

That such different results should emerge from these two factions says more about the different dynamics of animation and comics than anything else. Famous' version of Little Lulu is not at all like John Stanley's. A comparison reveals some self-evident but important truths about what John Stanley brought to the table as a writer and cartoonist.

Thanks to YouTube provider Kevin Martinez, you can watch all 26 of the Famous "Lulu" shorts online, for free. He's gone to the trouble to restore original title sequences, when the elements were available. Though most are sourced from retitled 1950s TV prints, they're nice-looking versions, and offer a generally very good way to assess this large chunk of animation product.

You can view a playlist here (updated link added August 3, 2024).

The biggest flaw of the Famous "Lulu" cartoons reflects the studio's most telling problem, which grew larger as the 1940s ended. Famous' reliance on stock formulas and scenarios slowly drained the life out of a promising cartoon studio. As characters such as Little Audrey, Casper the Friendly Ghost, Baby Huey and Herman and Katnip dominated the Famous output, so did recycled plots, gags and story arcs.

Thus, when you've seen one Herman and Katnip, you've really and truly seen them all. Famous picked up some steam in the later 1950s, largely thanks to the innovative writing and design of Irv Spector, whose mordant wit and angular draftsmanship pushed Famous into the cartoon modern world. Resulting cartoons like

Finnegan's Flea,

Cool Cat Blues and

Chew Chew Baby (the latter not currently viewable on YouTube, alas) offered a low-budget, eerie and comically vibrant alternative to the generally flagging state of theatrical animation.

The Famous Studios of 1943 was feeling its oats, and with such high-profile licensed properties as Popeye, Superman and Little Lulu, had considerable commercial clout. The series launched with impressive color ads in the movie trade magazines:

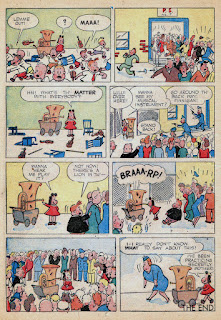

Famous was never 100% sure what to do with Little Lulu. She was too low-key a character for wild exaggerated slapstick; she was too earthy for saccharine-sweet cute cartoons (thank the deity of your choice). Their initial impulse was to make Lulu a seemingly oblivious, understated trouble-maker. Charmingly voiced by Cecil Roy (a female voice talent who did several Famous characters), the animated Lulu was, initially, fairly close to the early John Stanley version.

Less impish than Stanley's first iteration, the early Famous Lulu identifies herself as a child who's just curious about the ways of the adult world--and a bit baffled as to why her innocent actions make her parents, and other adults, so angry and perplexed.

Like Stanley's Lulu, she is subject to frequent spankings. Like the Buell original, she is a subdued trouble-maker--an agent of chaos who is rarely aware of the effect of her actions. She innocently heckles the circus acts in

Hullabalulu (1944), aggravates a train porter (1947's

Loose in a Caboose), a department store manager (

Bargain Counter Attack, 1946), a sleazy press photographer (1945's

Snap Happy), a nearly sociopathic golfer (1947's

Cad and Caddy) and, most frequently, her long-suffering father.

These male adult characters, usually voiced by Jackson Beck (best-known as the voice of Bluto in the Famous

Popeye cartoons), tend to look, think and act alike. In some instances--particularly the

Lulu cartoons directed by Bill Tytla--the angered adult's pursuit of Lulu becomes nightmarish, more akin to the notorious 1964 classroom scare film

The Child Molester than to light-spirited cartoon hijinx.

Lulu's early companions in the Famous series are a stereotyped black maid, Mandy, and a cartoon mutt who resembles an escapee from the Friz Freleng stock company at Warner Brothers' cartoon studio. Despite Mandy's horrifying dehumanized appearance--a black button nose and lips akin to Fred Flintstone's five o' clock shadow--she is a strong character, and one longs, in later cartoons, for a less offensive variant of her.

Similarly solid characters are sorely lacking in the Famous

Lulu cartoons. Stock figures are in great supply, and, as the series progresses, so are stock situations. The finest

Lulus come early in the series.

Hullabalulu is a beautifully timed, amusing cartoon, with a simple situation milked for all it's worth.

Lulu in Hollywood, the fourth cartoon in the series, achieves moments of deadpan brilliance. 1944's

I'm Just Curious offers a charming original title song, a strong, unusual structure, and the most vivid sense of the Lulu character in the Famous films.

Speaking of theme songs, the series' theme tune boasts a unique distinction; it was the only theatrical cartoon theme to be recorded by a modern jazz artist. Pianist Bill Evans recorded "Little Lulu" with his trio in December, 1963; the live performance kicks off Evans'

Trio '64 album. (I still hold out hope for the discovery of an unissued Sun Ra Arkestra rendition of the Herman and Katnip theme.)

Rather than examine each cartoon for its relation to John Stanley's work, let's focus on the one Famous

Lulu short that comes closest to the resultant comics version.

Beau Ties, released in April, 1945, concurrent with Stanley's first

Lulu comic book (itself cover-dated June, 1945), is the only short in the series to play off the relationship between Lulu and Tubby Tompkins (called "Fatso" in this animated cartoon).

Tubby makes minor appearances in a few other Famous cartoons, but

Beau Ties marks his only significant role in the series. Voiced by Arnold Stang, "Fatso" shows some of the Quixotic self-assurance and duplicity of Stanley's Tubby. Though he quickly turns coward, and is physically dominated by Lulu, "Fatso" is an eerie prediction of the Stanley character.

Famous' failure to seize upon the natural relationship between Lulu and Fatso/Tubby is the series' greatest tragedy. Although the cartoon traffics in the super-exaggerated, larger-than-life action available to 1940s animated cartoons, it is careful to focus on the relationship of the two characters. They are not stock antagonists, as are the menacing, burly adult men who frequent the series. Their relationship has some real human stakes, and though it's all played for laughs, the viewer leaves with the impression that these two children genuinely like each other.

As the Famous

Lulus degenerate, predictable and highly moralistic fantasy sequences become part of a joyless routine. Lulu's lack of interest in music practice, in 1947's

Musica-Lulu, sends her to a nightmare world of judgment and menace. Her attempted truancy in

Bored of Education (1946) climaxes in a pro-education fantasy sequence set to the jazz standard "Swingin' on a Star." Lulu's banishment from comic book reading, in 1947's

Super-Lulu, sets off a dream sequence that mashes up "Jack and the Beanstalk" and the tropes of super-hero comics.

This lapse into formula was, alas, SOP for post-war Famous Studios. Though the cartoons are beautifully animated, and have moments of mild inspiration, their cessation of original themes, approaches and ideas become stultifying.

There are exceptions to this rule.

Bargain Counter Attack is hard-edged chase comedy worthy of Warner Brothers' Friz Freleng. The penultimate Lulu cartoon,

The Baby Sitter, captures some of the vibe of Robert McKimson's early directorial efforts at Warners. Such cartoons show that Famous still had some comedic

cojones, despite the falling-apart of their original high ambitions.

When Famous' five-year license on Lulu expired, in 1948, the studio, in an eerie reprise of Lulu's own creation, slapped together a simulacra called Little Audrey. Audrey immediately went to bed with the Famous formula machine. With her horrifying, mechanical laughter and the cloying morals of her fantasy sequences, the Little Audrey cartoons are, to quote Thad K., "funny as AIDS or nuclear war."

By this time, John Stanley and his crew really and truly owned Little Lulu and her world. Famous would attempt two more "Lulu" cartoons in the early 1960s--each adapted from a John Stanley comic book story. You can find posts about those cartoons--with links to the films themselves--elsewhere on this blog.

My experience of viewing these 26 cartoons gave me an important insight re John Stanley's work. His sense of humor, his characters, situations and stakes are entirely earthbound and capable of happening to you or I. Stanley siphoned off an evident interest in the supernatural into the series of on-the-fly stories Lulu tells to her bratty next-door-nabe, Alvin.

Ghosts tiptoe into some of the early Stanley

Lulu stories, most notably 1946's "The Haunted House," also readable elsewhere herein. By 1948, Stanley is careful to couch such incidences in a cloud of ambiguity. In one of his masterworks, 1954's "The Guest in the Ghost Hotel" (

Tubby #7), the vagary of events is handled with great narrative skill. Did the events of this story really happen, or did Tubby's runaway-train imagination cobble them together? Multiple readings of the story fail to ease its lovely ambiguity.

Because John Stanley's comedy is possible in our own world, it carries more weight. The high energy and wild exaggerations of the Famous

Lulu cartoons work perfectly in that context. As Carl Barks understood about his "Donald Duck" stories, such cartoony impossibility would not work on the printed page, or in an extended narrative with stakes. (Floyd Gottfredson also grokked this in his newspaper

Mickey Mouse narratives, from 1932 onward.)

Are Stanley's "Lulu" stories superior to Famous' cartoons because they're more earthbound? Yes and no. They work because you give a damn about the characters. Over the course of reading Stanley's "Lulu" stories, you get to know the characters, for good and bad. All their flaws and virtues are laid out. Their shortcomings become part of who they are, and we accept them because we know them.

In comparison, the Famous Lulu barely exists. Missing is that inner fire that makes a fictional character believable and engaging. We enjoy seeing her frustrate the ringmaster of the sleazy circus in

Hullabalulu because she's absolutely right in her chorus of "it's a fake!" We like her in

Beau Ties because she clearly cares for Fatso, despite himself. But she ceases to exist the moment her cartoons end.

Other animated characters, especially Warner Brothers' Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, were given rich shadings of character and motivation. Like Stanley's Lulu, they achieve a sense of relatable personality.

Stanley's Lulu, in contrast, stays alive in the reader's thoughts. She exists as a possible human being, and the events of her life are similar to ours. The darkness of her world also reflects our own experiences. In this regard, John Stanley's depressive vision worked a positive effect. Outcomes in his "Lulu" universe are often miserable, disappointing or deflating. When things work out, we share in the characters' joy. Their victories are hard-won, as are our own.

Thus, John Stanley's body of "Little Lulu" stories remain accessible, affecting and have currency, half a century (or more) since their creation. Famous' 1940s Lulu cartoons, though vivid, often charming and funny, fail to realize the potential of their character or her world, and substitute cheap laughs for moments that matter. As animated cartoons, they succeed, on a lesser level than the Warners output, and are worth seeing, warts and all.

To compare them to John Stanley's version of Little Lulu is, perhaps, unfair. But the geographical proximity of Famous' cartoons and Stanley's emerging version remains fascinating. They deserve at least footnote status in the John Stanley story.