Here are three of the four stories that comprise Four Color #120, which bears a publication date of October 1946. As ever, it's preferable to read these stories in color, as they were originally intended.

With this issue, John Stanley begins to take chances with the licensed characters of Marge Buell. This is the most New Funnies-like issue of Lulu. The story situations are quite akin to his contemporary "Andy Panda," "Oswald Rabbit" and "Woody Woodpecker" pieces.

They're much less about character-driven comedy than broad, escalating situations. That said, Stanley's growing awareness of the potential of the LL cast further flavors these innovative stories. While Stanley the artist still struggles with the rudimentary/bad design of the Marge Buell characters, Stanley the writer cuts loose and tries for belly laughs and broader strokes.

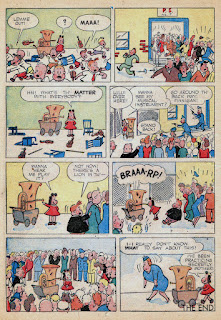

The issue's first (and longest) story, "Tuba Trouble," anticipates 1950s sitcoms. The narrative centers around a wacky decision Lulu makes, and sees through to its absurd but logical conclusion. Stanley had a knack for this kind of story, and would return to this template more often in the 1960s.

Stanley's sitcoms have more depth and patience than is the standard. In this potentially I Love Lucy-style narrative, he is careful to keep character quirks in the foreground.

There is always a sobering moment in Stanley's work. For "Tuba Trouble," it is the sequence on the top half of page 2. Tubby's notion that parents own their children, and that corporal punishment is inevitable, even for the misdeeds of his friends, adds that note of gravity prevalent in the Stanley universe.

This early on, the kids' interactions with adults still have anarchic tinges. The Lulu cast would become conformists to social mores (with the important exception of Tubby) by the turn of the decade. Here, Lulu thinks nothing of hurling gravel through a window, or of stealing a neighbor's lawn mower to exchange for that decrepit tuba. Of course, she has her own logical rationale for each action.

In this sense, the early John Stanley Lulu character is more like the Tubby of his 1950s stories. Tubby is far more passive in these earlier pieces. Once Stanley figured his master plan out, and assigned the self-deluded, self-justifying persona to Tubby, Lulu becomes a steadfast, feet-on-the-ground assayer of logic and reason. This was Stanley's greatest alteration of the Marge characters, and what makes them so far superior to her gag-cartoon iteration.

The tuba--and its audio pandemonium--is akin to Stanley's "Andy Panda" stories. It's easy to imagine that series' upstart, Charlie Chicken, being obsessed with the windy brass instrument, and causing a public panic with its startling farts.

It is, of course, funnier to have a meek little girl behind this wind-breaking, and for her to be blissfully ignorant of the effect her tuba efforts have on the world around her. She simply wants to be included in her friends' pitiful music making. To the boys, music-making is an enforced torment, demanded of them by their seemingly irrational parents/owners. The beat cop's spiel about Sherlock Holmes may fortify Tubby and Eddie for the moment, but in the long run it's sheer hell for these kids, this music practice routine. The violin is a messenger of misery in John Stanley's world. Did he dislike the instrument? One wonders.

A half-page scene of public chaos highlights the penultimate page. Far funnier, though, is that page's second panel. We can only imagine the discordance produced by those kids. That Lulu's tuba-belching should outdo that cacophony is quite a feat.

Stanley aims for a dry humor in "Tuba Trouble." It succeeds in understating its turbid events. The effect is quite unlike his frenzied farces of the 1960s.

Next is "Indian Uprising." My apologies to any Native American readers of Stanley Stories. I have read all but three issues of John Stanley's output (and, thanks to Michael Barrier, I will soon have scans of those missing pieces). I have yet to see, outside of the notorious Li'l Eight Ball, a moment of outrageous ethnic caricature in Stanley's work.

After a gander at the opening image of the first Famous Studios Little Lulu cartoon, Eggs Don't Bounce, Stanley's Li'l Eight Ball stories seem much milder in comparison. The one ethnic group Stanley used in his work were Native Americans. Making light of "injuns" far outlasted other ethnic ribbings. Only in the last 10-15 years has mass media backed away from the "how! ugh!" vision of the "redskin."

No actual stereotyped Indians appear here--just their affect. The kids' fantasies are fueled by the Hollywood crap that encouraged these stereotypes. This vicious circle, whether consciously planned or not, fuels one of the most topsy-turvy stories in Stanley's Lulu canon.

Few of Stanley's Little Lulu stories are as riotously funny as "Indian Troubles." Sublime comedic timing and techniques abound--once again relayed with understatement. From Alvin's quiet defacement of a tulip patch to Lulu's word-for-word explanation (repeated for the authorities) of how her father got a mannequin head, instead of a cabbage, every moment is beautifully downplayed.

Tubby's boyishly vicious fantasy of the Old West, at story's beginning, gives further shading to his yet-unfinished persona. In this moment, this early Tub aligns with the mid-1950s model. As said, only the kids' use of iodine to darken their skin alludes to the "injun" theme. Notably, the kids are on the side of the Native Americans. They love the outlet to wreak havoc that the "redskin" persona provides.

Even so, the children never lose their mid-century suburban American-ness. The contrast of their attempts to break from the societal mold, and the irritation and embarrassment they cause the adults around them, is sublime. No need to push the PC Alert Button this time!

I've skipped the amusing "Newspaper Business" to conclude with an early instance of Stanley's meta-fairy tales. "Little Lulu and the Seven Dwarfs" is notable for its parody of the then eight year-old Walt Disney animated feature. With this cultural landmark as a compass, Lulu's selective corruption of remembered events and invented, personalized touches is laid bare for the reader to savor.

Notice, as well, the second of John Stanley's witches. The first appeared in this 1945 Oswald Rabbit story. While clearly based on the source material parodied, this ur-witch, who meekly appears in the story's denouement, roughly anticipates his 1950s creation, Witch Hazel.

Stanley indulges in a rare quotation from pop culture. He has the dwarfs singing their signature song from the Disney Snow White feature, "Heigh Ho." Litigation would ensue if anyone did this now, but in 1946, it probably passed by completely un-noticed.

Stanley's use of the song fuels a brutally comedic sequence in which Lulu is trampled by the dwarfs as they come and go from their mining work. This sequence ends with a sublime instance of discrepancy, via Lulu's understatement of the invented events of her imagination:

Lulu never strays far from her current reality in these on-the-fly fairy tales. Her inclusion of poison cookies, a reflection of a recent baking episode, informs her parody of Snow White, and tidily ties the story's events together.

This narrative decision ruins her appetite for the cookies she's baked--and thus the story ends, with story-teller berating herself for being too inventive.

As work concludes on the long-awaited Carter Family graphic novel, I will be away from the blogosphere for the next month or so. When I emerge, I hope to have some fresh Stanley material to share with you. In the meantime, be well and prosper!