While I couldn't access this machine, I read books and did other things once so common-place, pre-internet. Among these readings was a revisit to the three volumes of Drawn + Quarterly's complete reprinting of John Stanley's 1960s work, Melvin Monster.

I've found Melvin rough going, due to its intense emotional darkness. That darkness serves a purpose, as I've come to realize. It is a constant reminder that we're not in our world anymore. We're visiting a warped, refracted place that has recognizable aspects to us, but which is essentially alien.

Monsterville, the setting of Melvin Monster, is among John Stanley's most compelling fictional worlds. As was the case with too many of his personal projects, the series ended just when Stanley put most of its pieces in place.

We never get a complete sense of what Monsterville is like--as we do with the Northeastern city that the world of Little Lulu occupies. Certain locales are ritually revisited, but we're left with the sense that there is much yet explored or documented. Nine quarterly 36-page comic books are all we have. Much of their action occurs inside one home, or on its immediate premises.

Though they're sometimes just sketched in roughly, much is said via the series' dilapidated urban-suburban settings. They are a grotesque mirror of the world of Little Lulu, Thirteen Going on Eighteen and other Stanley series.

This curious societal shambles--an acute mixture of order and chaos--is the backbone of Melvin Monster. While it borrows from Charles Addams' magazine cartoons, and captures the zeitgeist of the mid-'60s TV monster craze (The Munsters, The Addams Family), the atmosphere of Melvin is more deliberate, logical and haunting. It helps us understand--and ultimately accept--the emotional minefield of this brutal-yet-orderly world.

The basic affect of this world is recognizable--residential streets with houses, sidewalks, lawns, fences and evidence of public utilities. There are apparent businesses, at least one schoolhouse, and outlying, off-limits areas, shrouded by deep woods, that insulate Monsterville from the adjacent world of "human beans."

In early issues of Melvin Monster, we see the "human bean" world quite often. Melvin, our identification figure in these stories, is curious about this more orderly, less chaotic mirror-world, and wants to be a part of it. He is a reluctant member of Monsterville--he's there by birth only, and he doesn't cotton to its prejudices and values.

Yet Monsterville seems patterned on the "human bean" world, and exists as a corruption of that equally chaotic society.

This recalls the awkward-but-fascinating "Tales of the Bizarro World" series which ran in the DC Comics title Adventure Comics in the early 1960s. Sometimes scripted by Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel, the "Bizarro World" stories set an impossible, petrifying standard. Everything "right" had to be wrong, and vice versa.

This abnormal-as-the-norm bias also informs the monster TV sitcoms mentioned above, and tinges Stanley's Monsterville. This comedy of free-wheeling anti-conformism seems apt for anxiety-packed Cold War America. Average Joe and his offspring/spouse could enjoy some harmless chuckles at the addled mirror this school of comedy offered.

While none of these commercial efforts pointedly mocks the conformism of early '60s American life, the intent is still there. By making light of the bizarro-type characters' conformation to bass-ackward rules of disorder, these mass media outlets poke polite holes through the fabric of what we call structured society. (Thank you, Vermont Ferret, for this photograph.)

John Stanley is an outstanding humorist, and a superb storyteller, but he was not Harvey Kurtzman. He does not set out to show that the emperor is buck nekkid. If anything, he's on the side of the sublimely deluded, and loves to wind them up and watch them go.

The main gimmick of Melvin Monster is that Melvin is the only "normal" figure in an abnormal world. He experiences Monsterville as you or I might, were we dropped into it, and expected to thrive. He is aware of his difference, and that he is an outsider. Yet he's not a Quixotic comical figure, like Tubby Tompkins and other signature Stanley characters. He seems to be the voice of reason in this dark wilderness.

Because of his otherness, he is exquisitely sensitive, and a moving target for the hostilities of the "normal" world of Monsterville. From his ill-tempered, risible "Baddy" and passive "Mummy" to the homicidal schoolmarm, Miss McGargoyle, to friends such as the witch-in-training, Little Horror, Melvin's daily life is filled with hostile encounters with supposed friends and family.

He might as well be a closeted gay teenager in 1960s Birmingham, Alabama. Only by pretending to follow the norms of a world he dislikes and fears can Melvin make it through a day in Monsterville.

In one telling sequence, we're shown a scene of domestic distress caused by Melvin's affection for "human bean" ways:

The last page of the last issue of Melvin touchingly plays upon this dichotomy:

On this heart-breaking scene of wish fulfillment thwarted, let's begin our visual tour of Monsterville...

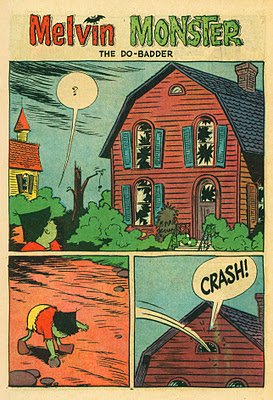

The first page of the first story offers significant exterior and interior views of average life in the community of Monsterville:

Decay, disorder and visual chaos are established straight away. The landscape of residential Monsterville would alter significantly in later issues, while retaining these key assets.

Here, we see stock Gothic mansions crowded together in an overgrown, foreboding terrain. Inside these homes, if Melvin's abode is typical, are broken windows, cracked plaster, peeling paint or wallpaper and threadbare carpets. These visual clues give us a strong sense of dust, mildew, dampness and grime. This house would probably smell funny, and give allergy sufferers a sneezing attack.

Again, this is on par with contemporary monster-sitcoms, especially The Munsters, which premiered on American TV in the fall of 1964. Given the lag in production time for magazines and comic books, it's very possible that Stanley either saw The Munsters, or had it suggested as a possible springboard for an original comics series.

Like Herman Munster (played with gentle charm by Fred Gwynne), Melvin's "Baddy" has a night job. His vocation smacks more of the "Bizarro World" than the TV sitcom:

This scene, from the second issue of Melvin, offers a rare full view of the house's front yard, and its entryway to the street. As with the "Bizarro World" series, rules dominate the world of Monsterville. Order and disorder fight one another, and typically cancel one another out.

The same basic problem plagues both Melvin Monster and the "Bizarro World" series: there must be some sort of societal order, but how does a community that thrives on anarchy still have rules? These rules are strictly followed--especially in the "Bizarro World," which has its own, often-repeated code:

The logic-implosion of this Code is a detour I'm not willing to take in this essay. Suffice to say that Stanley's Monsterville is a more loose-knit community. Traditions and rules of monster conduct are often recited and referred to, but the stakes for a non-conformist are much lower here.

More street views of suburban Monsterville show evidence of public utilities, and thus societal structure. They have paved sidewalks, fire hydrants, telephone poles and power lines:

No cars, trucks or other engine-based vehicles are seen in Monsterville. Melvin's friend, Little Horror, has a variety of witches' brooms, but I doubt those would merit the civil inclusion of traffic lights, which nonetheless exist in this community:

Monsterville appears to have at least one newspaper, seen here:

Melvin's home has a television. Whether this is local programming, or "human bean" TV, picked up via aerial, is never made clear:

Though yard neglect is the standard here, property lines are denoted by fences and other markers:

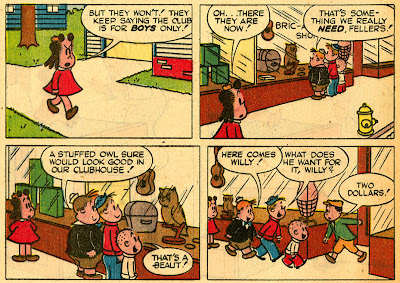

These settings are sketchy, vague and generic. They are akin to the similar environs of Little Lulu and Thirteen Going on Eighteen:

Stanley cares far less about detailed settings, as a writer-cartoonist, than do his collaborators. Irving Tripp (seen above, in the Lulu sequence) and Bill Williams (below, in an example from Dunc 'n' Loo) who endow the fictive-real worlds of John Stanley with solid, substantial detail:

To Stanley, the characters were the story. Though he does indulge in more atmospheric landscapes in Melvin Monster, he keeps the settings as low-key as possible throughout the series. The one aspect of Monsterville lushly detailed are its tangled, shadowy landscapes and woodlands. Those forlorn scenes of open fields and thickets, dense with overgrowth and neglect, are a haunting visual component of the series.

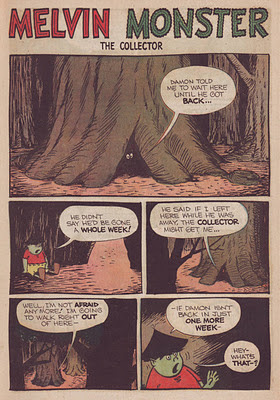

Stanley's scenes of the woods, in particular, achieve a sense of aching desolation comics wouldn't see again until the publication of Charles Burns' Black Hole:

Stanley had a knack for cartooned landscapes, seen in his 1940s work for Little Lulu and his original series "Peterkin Pottle" and "Jigger and Mooch." This sensibility informs many of the great 1950s stories he both wrote and drew, including the seminal story "The Guest in the Ghost Hotel." You can find this story elsewhere on the blog, or in at least two current reprints.

In the pastoral scenes of Melvin Monster, Stanley flourishes as an expressive cartoonist. The mood of those shaggy fields, and those clusters of trees and thickets, bring this fictive world to life.

Before Stanley abandoned the connection to the world of "human beans," he played with the contrast-complement of these two simultaneous universes, as in this four-page story from issue 3:

Melvin Monster is a blend of familiar John Stanley events and archetypes. A strong interest in horrific themes is evident throughout his career. An overwhelming amount of Little Lulu's improvised fairy tales have horror motifs. The most recurrent of these, Witch Hazel, has a doppelganger in Melvin's Miss McGargoyle.

This choice of subject matter was not unusual for Stanley. Shoved into the forefront of Melvin Monster, macabre elements become the norm, as seen through the eyes of a developing child who struggles to accept or understand them.

Despite the heaviness and harshness of its ritual events, there is a playful, lighter side to Melvin Monster. A key to appreciating this series is that we realize this is not our world. It looks somewhat similar, but it plays by different rules. Black is white and good is bad in Monsterville. Parents would tend to be gruff, abusive and moody; physical violence, bullying and other assorted assaults are the commerce of daily society.

Stanley doesn't make a big deal of any of this. He presents it straightforwardly, without much back-story or build-up. We aren't constantly reminded of the dos and don'ts, as in the "Bizarro World" series. Thus, we must make peace with the Medieval cruelty of Monsterville, and appreciate what good citizens its residents truly are, given their circumstances.

Monsterville is a slice of John Stanley's world that ended far too soon. The glimpses and passing scenes we get, in the nine issues of Melvin Monster, establish it enough that we can fill in the missing pieces--as Stanley surely would have, had the series lasted longer. It is a troubled and troubling world, but one worth our attention.

P.S.: This is a rare example of a John Stanley series that's been recently reprinted in full, via Drawn + Quarterly's lush hardcover three-book set. The reproduction in those volumes is far, far better than the motley scans seen here. If you don't own those three books, please consider buying them. Consider this essay a compliment to those D+Q volumes.

P.P.S.: RIP, Megaupload. The bad guys have won a big one here... The extent of how much this sucks will no doubt grow larger in the next few days. The Internet, as we once knew it, is rapidly changing for the worse...

1 comment:

Your remarks on the logical problems of Monsterville and Bizarro World reminded me of the second series of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, in which Reggie, disgusted with suburban, consumerist life, opens a shop called Grot, with the slogan “Everything sold at Grot is guaranteed to be completely useless,” only to see within two years, to his horror, that Grot has made him one of the wealthiest men in Europe.

Post a Comment