As I dig deeper in the largely un-documented history of John Stanley's comics writing, I find a fair share of near-misses and wanna-bes.

Here and there I get clues. In an interview published in one of the Little Lulu Library sets, artist Irving Tripp mentions one Charlie Hedinger, who he credits with penciling the early issues of Little Lulu that Tripp worked on.

Tripp guesstimates that he came on board in "possibly the late 1940s." Furthermore, he states that Hedinger transitioned to a writer position in "I would say mid- or late 1950s."

Tripp provides no hard facts and no exact dates. He stayed with Little Lulu long after John Stanley's departure in 1959 (which he remembers as "what must have been the middle 1950s").

Long before Stanley's exit, Tripp took on the entire art workload for Lulu. This leaves Charlie Hedinger as a possible suspect for the mysterious "near-Stanley" stories that I've discussed and occasionally presented on this blog. Tripp also mentions the writer Carl Hubbel, who co-wrote stories with his wife, Virginia.

Thanks to information from comics history scholar Steven Rowe, I've learned that Hedinger's name is mis-spelled throughout the published interview as "Heddinger." The Grand Comic Book Database offers THIS information on Charles Hedinger. They list only 10 credits, including one story apiece for Popular Comics, New Funnies and Our Gang Comics. (These, certainly, cannot be his only published works!) He is not named in this one-time listing of the Little Lulu personnel.

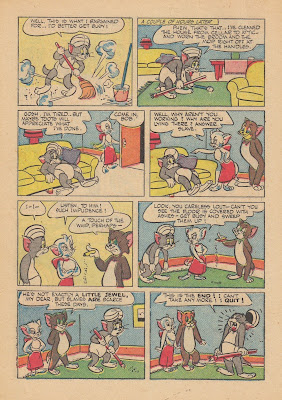

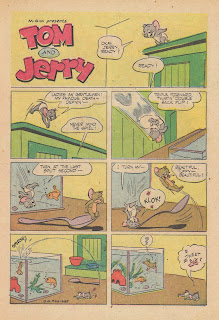

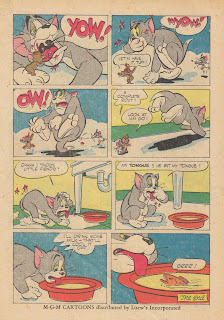

For today, let's enjoy the stylish, accomplished and truly comic artwork of Bill Williams--the single best cartoonist who ever worked with John Stanley. This story, the lead strip in the 7th Henry Aldrich comic book, smacks of John Stanley's touch. It strongly resembles one of Stanley's early 1960s Dunc 'n' Loo stories--and not just for Williams' essential input. The basic situation (hero is saddled with extremely difficult un-socialized wild-card; squirms in discomfort as oddball is too stubborn to be placated; chaos ensues) is a time-tested Stanley Scenario.

Other tells include sound effects in speech balloons, "fixed camera" sequences, silent sequences, wild physical action, crowd scenes and graphically playful/aggressive sound effects.

Read it and draw your own conclusions:

This is a funny, vivid story, with most of the humor rooted in each character's distinct personality, and its attendant quirks. The staging seems akin to Stanley's approach, as does the lack of chemistry between Henry and Jessica. They are two unlike beings forced upon each other, as with Little Lulu's Tubby and his mini-me relation, Chubby.

The story's circular ending, complete with a the-end that happens on an off-beat, further seem to point in Stanley's direction.

As ever, your two cents are quite valuable to me. Drop me a note and let me know what you think.