Thursday, February 24, 2011

Beatniks, Bongos and Bourgeois Boobys: selections from Kookie #1, 1961

1961 marked a turning point in John Stanley's comic book career. He wrote the last issues of his final significant licensed-character series, Nancy and Sluggo. From then on, with three exceptions, Stanley never again worked with anyone else's characters.

It was a shot in the arm for Stanley. His two years on the Nancy title, added to 15 years on Little Lulu, left him apparently (and understandably) weary of the task of adapting outside characters to the comic book narrative form. Save for mid-1960s comics adaptations of Alvin and the Chipmunks and Clyde Crashcup, and 1969's curious Choo-Choo Charlie one-shot, Stanley only created original concepts, characters and series from 1962 forward.

His earnest attempts to get original series going in the late '40s failed. Although "Jigger and Mooch" and "Peterkin Pottle" have their rightful admirers, they simply didn't cut it, sales-wise and audience-wise, back in the day. It may have discouraged Stanley from using precious time--energy that could more productively go into Little Lulu and his other steady gigs--on the high-stakes risk of floating unknown creations.

Thank goodness the comics industry was in a state of flux in 1961. Super-heroes noodged their way back onto the shelves, while steadfast genres such as crime, western, romance and what passed for horror, post-Comics Code, dwindled or died. War comics continued to sell, as did many varieties of action-adventure and humor.

At this time, Stanley and his family lived in Greenwich Village. Perhaps this daily exposure to the bohemian vibes of that ultra-hip neighborhood inspired Stanley to try something different. For the first time in his career, Stanley created a title that was clearly aimed not at kids but at young adults, teens and college students.

Kookie, launched two months after Stanley's first original success in comics, Dunc 'n Loo, proved a quick flop. Both were collaborations with Stanley's finest artist, Bill Williams. Why one clicked and the other didn't is puzzling.

Perhaps Kookie was a little too libertine for mainstream comics. It's among Stanley's only comics with any acknowledgment of adult desires. Kookie is cast as a sorta-Candide of the espresso house scene. Given time, her role would have been more well-defined. She is, certainly, no Little Annie Fanny, but she's a great deal more voluptuous--and inspires more, shall we say, grown-up reactions from her male pursuers and admirers--than any Stanley character, before or since.

By late 1961, when its first issue hit America's news stands, beatniks were a bit on the wane. The Beat Generation still existed, and some of its more notable authors and artists continued to create vibrant, striking work. But the whole scene was already reduced to a handful of popcult cliches--Maynard G. Krebs from TV's Dobie Gillis, Ernie Bushmiller's outrageous put-downs in the newspaper version of Nancy, and countless beatnik wanna-bes in popular fiction.

Stanley's take on the beat scene owes a little to Max Shulman's Dobie Gillis sitcom, which it resembles in its cramped, grubby urban settings and with its risible, exaggerated characters. Dobie was only peripherally related to the beat scene, but the program's snappy pace and colorful patter has much in common with Stanley's work of 1962.

Here's "The Scene," the first story from the first Kookie issue. I posted a story from the second, and last issue, here. In that post, I posit some other theories about Kookie's marketplace failure.

But first, dig that righteous cover! Bill Williams' beautiful cartooning looks gorgeous in watercolor or gouache, whichever medium it's painted in.

Here's the inside front cover gag--a format among John Stanley's fortes as a comics creator.

And now, "The Scene..."

"The Scene" is unusual for Stanley. Its narrative doesn't hinge on a single, escalating event. Rather, it paints a leisurely paced series of highly comedic vignettes--expertly designed to ease us into its quirky urban world.

Though Kookie is the star of the story, she isn't really its main focus. Like Jacques Tati's 1967 movie Playtime, "The Scene" isn't married to any one character or occurrence. Big things happen--roomie Clara's creative revenge on the bongo-mad dudes who plague her sleep; the wonderful beat poetry performance of Fleahaven; the entrance and exit of the two "bourgeois booby" richfolk; the epic cleaving of the sculptor Herman's three-story statue. Big characters crowd the stage, one after another, as Kookie watches and reacts.

Stanley does not condescend to his bohemian cast, nor exploit them for a cheap laugh. The buffoons of the piece are the two uptown types who wander into the world of Mama Pappa's expresso house--and pay for their slumming with social humiliation (witnessed by an audience who doesn't really notice or care) and a scorched leather car-seat.

Something decidedly different happens in the 18 pages of "The Scene." There's not another John Stanley story quite like it--which is a pity. "The Scene"'s expansive, democratic approach, and its creation of a world both gently and vigorously funny, suggests unfulfilled possibilities for this series (and for Stanley's work), had it lasted more than two issues.

1962 comics had to have an unrelated second feature, in order to qualify for postal distribution. "Bongo and Bop" was Stanley's solution to that need. It's a more hard-edged, brilliantly funny piece that anticipates the 1970s underground comix humor of Gilbert Shelton.

The urban landscapes of "A Breather" are familiar to Little Lulu readers. Unlike Stanley's scores of lark-in-the-park stories, this achieves a sublime level of character and black comedy, in five easy pieces (er, pages).

Bongo and Bop look somewhat alien and insectoid, with their berets, gaunt cheeks and oversized dark glasses, but Stanley once again doesn't treat them with condescension. They are a refreshing twist on his typical "Tubby Type." They're deluded, but susceptible to outside influence.

In the story's sublime ending, Bongo and Bop temporarily morph into "squares"-- until a lungful of carbon monoxide revives their true selves.

This return to form distinguishes Stanley's work. Most other humorists would have played the change to "normalcy" for boffo laffs, as if to say "See? This beatnik thing is just an affectation!" In John Stanley's world, you are what you are. Hero or zero, his characters are true to their tendencies and tics.

Stanley never again had--or gave himself--the luxury of pacing, nor the openness of his comedic attitude, that is evident in the brief life of Kookie. This is John Stanley at his warmest and most down to earth.

My next post will be the 200th for Stanley Stories. I hope to have something special to mark the occasion.

Friday, February 11, 2011

OCD Eating and a Convergence of Creeps: Nancy and Sluggo Summer Camp special pt. III (conclusion)

As promised, here is the conclusion of the 1960 Nancy and Sluggo Summer Camp shebang.

"The Dinner Belle" contrasts two schools of cognitive biases towards food: the anti-anorexia of Eadie and the smug entitlement of Camp directory Simply.

John Stanley, like Little Orphan Annie's Harold Gray, tended to give supporting characters Dickensian names--ones that sum up their shortcomings or hang-ups. In Simply's case, his smug, naive expectations fully justify this type-naming.

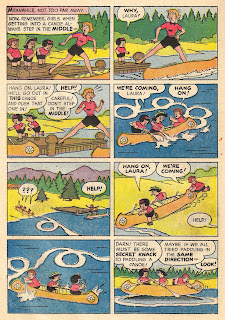

Everything in this rambling book comes to a head in "Lost in the Woods." All storylines intersect, and McOnion gets a terrifying-yet-appropos comeuppance.

Also like Harold Gray, John Stanley was a strong believer in comics karma. Gray's comeuppances are usually of a brutal nature. Stanley's threaten their characters, but never result in death or serious injury. Mind-fudgery and status demotion are typical results of Stanley's comic karma.

"Lost in the Woods" is by far the liveliest, most genuine sequence in this narrative. Stanley weaves together the book's various threads into a colorful, amusing fabric.

Moments of strong physical/verbal comedy include McOnion's Page-O'-Terror (the larger one here) and Nancy's mistaking of the wild bear's "GRRRRLLLLS" for an echo of her panic-stricken cry to her peers.

Also impressive is how Oona and her world is suddenly whipped into the formula. We're glad to see Sluggo reach Camp Fafamama intact, tho' too late in the game to achieve anything more than arrival.

Stanley would do far better in the second and last Nancy & Sluggo special, which I'll run here sometime.

Stanley brings this narrative to a rousing close with a finale that anticipates the over-reaching anarchy of It's A Mad, Mad, Mad World, while also suggesting the madcap quality of Frank Tashlin's or Jacques Tati's movies. Rollo Haveall is the stimulus of "The Tiger Hunt."

Rollo's need for/contempt for his protector-slave Keggly is darkly amusing. I find especially funny Rollo's move into Keggly's shirt.

The energy level surges in "The Tiger Hunt," after maintaining too much of an even keel in earlier pages. It's a welcome shot-in-the-arm, and shows Stanley finally investing something of value into this rambling piece.

After a rare and striking full-page panel, this story resolves on an almost-heart-warming note, with the emotional reformation of McOnion. He still has it in himself to send Sluggo one psycho post-card, and this event gives the book's finale a slight kicker of anxiety. (So does the last-panel Pledge to Parents!)

Inside-cover gag page, anyone?

My feeling about this book, overall, is a qualified Meh. It has its moments, and contains some striking anticipations of Stanley's more assured, solid 1960s comedy style. It feels a bit dashed-off, and shows the clear limitations of the "Nancy" cast, in Stanley's estimation. Nancy is a cipher--brilliantly manipulated in Ernie Bushmiller's comics world, but not a strong narrative leader. She exists as a foil for Bushmiller's factory-fresh gag machine, and nothing more.

Only when Stanley works with his creations--McOnion, Oona, and Tweak--does this narrative reach out and grab us. As Rob Clough notes in his recent review of the first Drawn + Quarterly Tubby book:

[b]y nature, Stanley was a world-builder; he felt the need to introduce various comic foils, friends and antagonists for his central characters. Part of that, I would guess, was Stanley’s way of giving himself raw material to work with; it’s his way of coming up with the variables for his comics writing formulas.

Stanley's Little Lulu casts a long shadow over his Nancy work. If I seem overly hard on this material, it's because it is regressive. Stanley did not grow as a writer with his time on Nancy. He reached into his recent past, and recycled formulas that had grown thin in Lulu's late issues. Though competent, and sometimes inspired, it lays listlessly next to Dunc 'n' Loo or his finest moments in Thirteen Going on Eighteen.

Half-strength Stanley is still far superior to most contemporary comics creators' efforts. Even when dialed down, Stanley couldn't help writing quality material. We remember McOnion's freaky pursuit of Sluggo, and the vagaries of Oona's mystical world. Other Stanley Nancy add-ons of note include the inept house-burglar, Bill Bungle (another Gray-hued name!) and Oona's self-obsessed miniature magician Uncle Eek.

I promise to be more enthusiastic in my next post, whatever it may be...

"The Dinner Belle" contrasts two schools of cognitive biases towards food: the anti-anorexia of Eadie and the smug entitlement of Camp directory Simply.

John Stanley, like Little Orphan Annie's Harold Gray, tended to give supporting characters Dickensian names--ones that sum up their shortcomings or hang-ups. In Simply's case, his smug, naive expectations fully justify this type-naming.

Everything in this rambling book comes to a head in "Lost in the Woods." All storylines intersect, and McOnion gets a terrifying-yet-appropos comeuppance.

Also like Harold Gray, John Stanley was a strong believer in comics karma. Gray's comeuppances are usually of a brutal nature. Stanley's threaten their characters, but never result in death or serious injury. Mind-fudgery and status demotion are typical results of Stanley's comic karma.

"Lost in the Woods" is by far the liveliest, most genuine sequence in this narrative. Stanley weaves together the book's various threads into a colorful, amusing fabric.

Moments of strong physical/verbal comedy include McOnion's Page-O'-Terror (the larger one here) and Nancy's mistaking of the wild bear's "GRRRRLLLLS" for an echo of her panic-stricken cry to her peers.

Also impressive is how Oona and her world is suddenly whipped into the formula. We're glad to see Sluggo reach Camp Fafamama intact, tho' too late in the game to achieve anything more than arrival.

Stanley would do far better in the second and last Nancy & Sluggo special, which I'll run here sometime.

Stanley brings this narrative to a rousing close with a finale that anticipates the over-reaching anarchy of It's A Mad, Mad, Mad World, while also suggesting the madcap quality of Frank Tashlin's or Jacques Tati's movies. Rollo Haveall is the stimulus of "The Tiger Hunt."

Rollo's need for/contempt for his protector-slave Keggly is darkly amusing. I find especially funny Rollo's move into Keggly's shirt.

The energy level surges in "The Tiger Hunt," after maintaining too much of an even keel in earlier pages. It's a welcome shot-in-the-arm, and shows Stanley finally investing something of value into this rambling piece.

After a rare and striking full-page panel, this story resolves on an almost-heart-warming note, with the emotional reformation of McOnion. He still has it in himself to send Sluggo one psycho post-card, and this event gives the book's finale a slight kicker of anxiety. (So does the last-panel Pledge to Parents!)

Inside-cover gag page, anyone?

My feeling about this book, overall, is a qualified Meh. It has its moments, and contains some striking anticipations of Stanley's more assured, solid 1960s comedy style. It feels a bit dashed-off, and shows the clear limitations of the "Nancy" cast, in Stanley's estimation. Nancy is a cipher--brilliantly manipulated in Ernie Bushmiller's comics world, but not a strong narrative leader. She exists as a foil for Bushmiller's factory-fresh gag machine, and nothing more.

Only when Stanley works with his creations--McOnion, Oona, and Tweak--does this narrative reach out and grab us. As Rob Clough notes in his recent review of the first Drawn + Quarterly Tubby book:

[b]y nature, Stanley was a world-builder; he felt the need to introduce various comic foils, friends and antagonists for his central characters. Part of that, I would guess, was Stanley’s way of giving himself raw material to work with; it’s his way of coming up with the variables for his comics writing formulas.

Stanley's Little Lulu casts a long shadow over his Nancy work. If I seem overly hard on this material, it's because it is regressive. Stanley did not grow as a writer with his time on Nancy. He reached into his recent past, and recycled formulas that had grown thin in Lulu's late issues. Though competent, and sometimes inspired, it lays listlessly next to Dunc 'n' Loo or his finest moments in Thirteen Going on Eighteen.

Half-strength Stanley is still far superior to most contemporary comics creators' efforts. Even when dialed down, Stanley couldn't help writing quality material. We remember McOnion's freaky pursuit of Sluggo, and the vagaries of Oona's mystical world. Other Stanley Nancy add-ons of note include the inept house-burglar, Bill Bungle (another Gray-hued name!) and Oona's self-obsessed miniature magician Uncle Eek.

I promise to be more enthusiastic in my next post, whatever it may be...

Labels:

McOnion,

Nancy,

Sluggo,

Stanley in the 1960s,

summer camp,

the evil rich

Monday, February 7, 2011

Lumpy Beds, Midget Magicians and Nose-Tweaking: Pt. II of the Nancy & Sluggo Summer Camp Special, 1960

On we go with the N&S summer camp epic.

We begin with two bed-related (and titled) vignettes, both which feature Stanley's answer to the Harvey Comics omnivore, Little Lotta--Eadie.

Eadie, who looks uncomfortably like Sluggo in drag, is a representative Stanley Type of the late '50s and early '60s--the abrasive, perpetually displeased misfit. These characters are typically socially self-destructive. Unlike the Tubby Type, this archetype is usually hostile and aggressive. This type is somewhat like Stanley's Evil Rich--except they're usually so disenfranchised they lack wealth of any kind.

Other examples of this type include Buddy from Dunc 'n' Loo and the whiny hypochondriac from the first issue of Linda Lark, Student Nurse.

It's a genuine relief to get away from Eadie, and return to the inexplicable world of Oona Goosepimple. This story features Oona's miniature magician Uncle Eek--a classic John Stanley wild-card character. Again, note the different artist for this sequence.

This story boasts an abundance of the Stanley trademark I've named "floating eyes in blackness." Stanley leaned on this device heavily in the later 1950s. Although it spared the artist(s) the chore of drawing scenes full of characters, the solid black frames entailed much brushing-in of black ink, in those pre-Photoshop daze of olde.

"Noses are Red" offers up yet another Stanley character-type--the Terrible Thwarter/Obstacle. Eadie redeems herself as the vicious victor of the nose-fixated bully, Tweak, and wins some social acceptance. Good on her!

Back to the... endless... nightmare... that is... McOnion...

A curious Christmas-themed filler follows McOnion's latest threat to Sluggo.

What better way to end this suite of abuse/discomfort-flavored stories than another dose of Rollo Haveall? Once again, Rollo's lack of human warmth and disdain for the welfare of others brings a chill to the proceedings.

Rollo is on the dark end of Stanley Street. He never learns--or changes--as a result of his karmic come-uppances. He dusts himself off and becomes just that much more horrid for his troubles.

Rollo really bothers me. Fittingly, this second of three installments ends with a punchline of physical discomfort, bordering on torment. Stanley really puts his Nancy cast through a decathlon of suffering.

I've come to feel that Stanley didn't care for writing Nancy. A general tone of gruffness, coupled with contempt for its characters, suffuses his work on the series. It may be that Stanley was burned out on this kid-centric school of comics.

After perhaps 1,000 Little Lulu and Tubby stories, Stanley certainly had the right to feel written out on the genre. His interest, post-Lulu, lay in older characters. Melvin Monster is over-powered by its adult characters; Dunc 'n' Loo and Thirteen focus on characters at or near puberty-age. The "Judy Junior" feature from Thirteen is focused on the theater-of-cruelty misfortunes that befall poor Jimmy Fuzzi. It's not at all the emotionally varied and integrated world of Little Lulu.

Stanley's lone "Bridget" page (easily found elsewhere on this blog) still displays a sharpness and skill with kid characters. It's over after 36 panels, and all too soon.

Stanley's last two comic book projects, Choo-Choo Charlie and O. G. Whiz (one issue each) have child protagonists, but narrative stakes and, in O.G.'s case, eccentric, aggressive adults, overpower the proceedings.

Back to Stanley's Nancy. Nancy has none of the humanity of Lulu Moppet. Sluggo falls short of the bar that Tubby Tompkins set. The rest of the characters, with the exception of the highly imaginative and inspired Oona Goosepimple, simply lack appeal and warmth. Oona's world, for all its flights of fantasy, is also a curiously cold, dangerous place.

Nancy's adult figures include some kind, helpful folks (e.g., the camp counselors in these stories), but the balance of them are dispassionate (Fritzi Ritz), sarcastic (Mrs. McOnion) or nutso (Mr. McOnion).

There is no sense of safety or comfort in the world of John Stanley's Nancy. Yes, there are brilliant sequences, and strong comedic set-pieces. We laugh at the comedy in Nancy, but we pay for it with the cruelty and emotional dis-connect of the characters.

It's not hack-work; almost nothing feels phoned in. Nancy was a necessary transition point for Stanley's work. Out of the emotional disconnect of this work would come the more character-rich Dunc 'n' Loo and the brutal-yet-deeply humane Thirteen Going on Eighteen.

We'll finish up this special issue next time.

We begin with two bed-related (and titled) vignettes, both which feature Stanley's answer to the Harvey Comics omnivore, Little Lotta--Eadie.

Eadie, who looks uncomfortably like Sluggo in drag, is a representative Stanley Type of the late '50s and early '60s--the abrasive, perpetually displeased misfit. These characters are typically socially self-destructive. Unlike the Tubby Type, this archetype is usually hostile and aggressive. This type is somewhat like Stanley's Evil Rich--except they're usually so disenfranchised they lack wealth of any kind.

Other examples of this type include Buddy from Dunc 'n' Loo and the whiny hypochondriac from the first issue of Linda Lark, Student Nurse.

It's a genuine relief to get away from Eadie, and return to the inexplicable world of Oona Goosepimple. This story features Oona's miniature magician Uncle Eek--a classic John Stanley wild-card character. Again, note the different artist for this sequence.

This story boasts an abundance of the Stanley trademark I've named "floating eyes in blackness." Stanley leaned on this device heavily in the later 1950s. Although it spared the artist(s) the chore of drawing scenes full of characters, the solid black frames entailed much brushing-in of black ink, in those pre-Photoshop daze of olde.

"Noses are Red" offers up yet another Stanley character-type--the Terrible Thwarter/Obstacle. Eadie redeems herself as the vicious victor of the nose-fixated bully, Tweak, and wins some social acceptance. Good on her!

Back to the... endless... nightmare... that is... McOnion...

A curious Christmas-themed filler follows McOnion's latest threat to Sluggo.

What better way to end this suite of abuse/discomfort-flavored stories than another dose of Rollo Haveall? Once again, Rollo's lack of human warmth and disdain for the welfare of others brings a chill to the proceedings.

Rollo is on the dark end of Stanley Street. He never learns--or changes--as a result of his karmic come-uppances. He dusts himself off and becomes just that much more horrid for his troubles.

Rollo really bothers me. Fittingly, this second of three installments ends with a punchline of physical discomfort, bordering on torment. Stanley really puts his Nancy cast through a decathlon of suffering.

I've come to feel that Stanley didn't care for writing Nancy. A general tone of gruffness, coupled with contempt for its characters, suffuses his work on the series. It may be that Stanley was burned out on this kid-centric school of comics.

After perhaps 1,000 Little Lulu and Tubby stories, Stanley certainly had the right to feel written out on the genre. His interest, post-Lulu, lay in older characters. Melvin Monster is over-powered by its adult characters; Dunc 'n' Loo and Thirteen focus on characters at or near puberty-age. The "Judy Junior" feature from Thirteen is focused on the theater-of-cruelty misfortunes that befall poor Jimmy Fuzzi. It's not at all the emotionally varied and integrated world of Little Lulu.

Stanley's lone "Bridget" page (easily found elsewhere on this blog) still displays a sharpness and skill with kid characters. It's over after 36 panels, and all too soon.

Stanley's last two comic book projects, Choo-Choo Charlie and O. G. Whiz (one issue each) have child protagonists, but narrative stakes and, in O.G.'s case, eccentric, aggressive adults, overpower the proceedings.

Back to Stanley's Nancy. Nancy has none of the humanity of Lulu Moppet. Sluggo falls short of the bar that Tubby Tompkins set. The rest of the characters, with the exception of the highly imaginative and inspired Oona Goosepimple, simply lack appeal and warmth. Oona's world, for all its flights of fantasy, is also a curiously cold, dangerous place.

Nancy's adult figures include some kind, helpful folks (e.g., the camp counselors in these stories), but the balance of them are dispassionate (Fritzi Ritz), sarcastic (Mrs. McOnion) or nutso (Mr. McOnion).

There is no sense of safety or comfort in the world of John Stanley's Nancy. Yes, there are brilliant sequences, and strong comedic set-pieces. We laugh at the comedy in Nancy, but we pay for it with the cruelty and emotional dis-connect of the characters.

It's not hack-work; almost nothing feels phoned in. Nancy was a necessary transition point for Stanley's work. Out of the emotional disconnect of this work would come the more character-rich Dunc 'n' Loo and the brutal-yet-deeply humane Thirteen Going on Eighteen.

We'll finish up this special issue next time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)