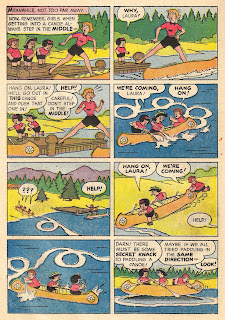

On we go with the N&S summer camp epic.

We begin with two bed-related (and titled) vignettes, both which feature Stanley's answer to the Harvey Comics omnivore, Little Lotta--Eadie.

Eadie, who looks uncomfortably like Sluggo in drag, is a representative Stanley Type of the late '50s and early '60s--the abrasive, perpetually displeased misfit. These characters are typically socially self-destructive. Unlike the Tubby Type, this archetype is usually hostile and aggressive. This type is somewhat like Stanley's Evil Rich--except they're usually so disenfranchised they lack wealth of any kind.

Other examples of this type include Buddy from Dunc 'n' Loo and the whiny hypochondriac from the first issue of Linda Lark, Student Nurse.

It's a genuine relief to get away from Eadie, and return to the inexplicable world of Oona Goosepimple. This story features Oona's miniature magician Uncle Eek--a classic John Stanley wild-card character. Again, note the different artist for this sequence.

This story boasts an abundance of the Stanley trademark I've named "floating eyes in blackness." Stanley leaned on this device heavily in the later 1950s. Although it spared the artist(s) the chore of drawing scenes full of characters, the solid black frames entailed much brushing-in of black ink, in those pre-Photoshop daze of olde.

"Noses are Red" offers up yet another Stanley character-type--the Terrible Thwarter/Obstacle. Eadie redeems herself as the vicious victor of the nose-fixated bully, Tweak, and wins some social acceptance. Good on her!

Back to the... endless... nightmare... that is... McOnion...

A curious Christmas-themed filler follows McOnion's latest threat to Sluggo.

What better way to end this suite of abuse/discomfort-flavored stories than another dose of Rollo Haveall? Once again, Rollo's lack of human warmth and disdain for the welfare of others brings a chill to the proceedings.

Rollo is on the dark end of Stanley Street. He never learns--or changes--as a result of his karmic come-uppances. He dusts himself off and becomes just that much more horrid for his troubles.

Rollo really bothers me. Fittingly, this second of three installments ends with a punchline of physical discomfort, bordering on torment. Stanley really puts his Nancy cast through a decathlon of suffering.

I've come to feel that Stanley didn't care for writing Nancy. A general tone of gruffness, coupled with contempt for its characters, suffuses his work on the series. It may be that Stanley was burned out on this kid-centric school of comics.

After perhaps 1,000 Little Lulu and Tubby stories, Stanley certainly had the right to feel written out on the genre. His interest, post-Lulu, lay in older characters. Melvin Monster is over-powered by its adult characters; Dunc 'n' Loo and Thirteen focus on characters at or near puberty-age. The "Judy Junior" feature from Thirteen is focused on the theater-of-cruelty misfortunes that befall poor Jimmy Fuzzi. It's not at all the emotionally varied and integrated world of Little Lulu.

Stanley's lone "Bridget" page (easily found elsewhere on this blog) still displays a sharpness and skill with kid characters. It's over after 36 panels, and all too soon.

Stanley's last two comic book projects, Choo-Choo Charlie and O. G. Whiz (one issue each) have child protagonists, but narrative stakes and, in O.G.'s case, eccentric, aggressive adults, overpower the proceedings.

Back to Stanley's Nancy. Nancy has none of the humanity of Lulu Moppet. Sluggo falls short of the bar that Tubby Tompkins set. The rest of the characters, with the exception of the highly imaginative and inspired Oona Goosepimple, simply lack appeal and warmth. Oona's world, for all its flights of fantasy, is also a curiously cold, dangerous place.

Nancy's adult figures include some kind, helpful folks (e.g., the camp counselors in these stories), but the balance of them are dispassionate (Fritzi Ritz), sarcastic (Mrs. McOnion) or nutso (Mr. McOnion).

There is no sense of safety or comfort in the world of John Stanley's Nancy. Yes, there are brilliant sequences, and strong comedic set-pieces. We laugh at the comedy in Nancy, but we pay for it with the cruelty and emotional dis-connect of the characters.

It's not hack-work; almost nothing feels phoned in. Nancy was a necessary transition point for Stanley's work. Out of the emotional disconnect of this work would come the more character-rich Dunc 'n' Loo and the brutal-yet-deeply humane Thirteen Going on Eighteen.

We'll finish up this special issue next time.

1 comment:

Thanks for the post. Your dedication is unparalleled.

Post a Comment