Have crowd, will please! Though I've just about exhausted the other John Stanley stuff, I still have the early Little Lulus to fall back on. I have bypassed these stories for a few years, as I've dug around in Dell/Western comics history, in search of unexplored Stanley stories.

My admiration for these stories is high. They represent an early plateau in John Stanley's comics career. After two years of sometimes-inspired knockabout comedies for the likes of New Funnies, Animal Comics and Our Gang Comics, Stanley had emerged a solid comedic writer and cartoonist, with a strong command of character, narrative stakes and dialogue.

Marge's Little Lulu was a prestige project--its source was not Hollywood animated cartoons. Low though Marge's comedy may have been, its publication in a national slick magazine gave it higher status than the likes of Andy Panda and Johnny Mole.

Not to knock those 1943-45 efforts! Stanley quickly proved himself the funniest creator on Western Publications' payroll. Carl Barks, on the West Coast, had yet to hone his comedic sense to the heights he would reach at the end of the decade. Walt Kelly and Stanley ran neck-and-neck as celebrators of comedic chaos.

Kelly can be devastatingly funny in these early comic book works. His more leisurely, wordy pace sometimes drowns his '40s comics in an excess of detail. Kelly would peak as a writer alongside Stanley, although in the higher-status world of syndicated newspaper comics.

John Stanley becomes an expansive, thoughtful writer via Little Lulu. Though the series quieted his more antic side, he gained much in terms of character development, escalating narrative stakes and the eternal balance of light and dark.

Missing from the mix is his hand as cartoonist. As of this issue, Stanley surrendered the finished artwork to the team of Charles Hedinger and Irving Tripp. This switch upset character creator Marge Buell, and is a visual low point in the series. Lulu wouldn't look right again until late 1949, when Irv Tripp and others had more or less perfected the look-and-feel of the feature.

Stanley had free rein to vary his story lengths in these Little Lulu one-shots. Though he had written several long narratives for earlier "Four Color" one-offs, many of those stories seem breathless and over-stuffed when compared to his Lulu work. In his short stories for the anthology titles, which had a strictly regimented page count, Stanley the improviser sometimes wrote himself out before a story was over.

Lulu gave him the privilege to make page count serve narrative. If a story needed to be 24 pages, or four, that was fine. This was exactly what he needed to grow as a writer.

In the three selections from this 52-page magazine, we have stories of 16, 5 and 10 pages' length. The stories move at the speed required by their situations.

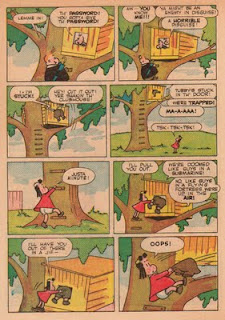

Early occurrences of classic Stanley themes appear in these stories. In the first, and longest, piece, "Fights Back With a Club," Stanley expands upon the gender-war of the previous issue's "He Can't Hurt Us." Added, this time, is the further stakes-raiser of cross-dressing. This introduces a whole new world of humiliation for the eternally proud, stubborn Tubby Tompkins... and brings peace to a war-torn world.

From trouser loss to unconvincing drag, Tubby fights in vain for his masculine dignity. That is, until he discovers that he kinda likes knitting doilies.

This is the first of many instances of cross-dressing by Tubby. A means to an end, this socially awkward action never really bore fruit for the self-deluded Tompkins. Did this stop him from donning dresses and ratty wigs? You already know the answer...

This cheerful act of vulnerability puts a kibosh on the boys v. girls business. In the unusual half-page panel that closes the story, males and females are joined together in productive harmony. While it's an amusing finale, the kids' comfort level in their united efforts is a smart, satisfying wrap-up to a story that bounces all over the comic/narrative map.

The anonymous child's closing comment, "I hope this here thing is washable!," anticipates the attitudes of Charles Schulz's early Peanuts characters. It's no stretch to imagine c.1952 Charlie Brown uttering this concern.

Today's second feature, "Brings Some Friends Home to Dinner," is a follow-up to the prior issue's "Stuff an' Nonsense," with its theme of animals that bring chaos to Lulu's barely-civilized life--and impact the status quo of her long-suffering parents.

The pigeons are antic aggressors in this short story, and they quickly become a threatening (and possibly permanent) element in Lulu's world. The story ends without resolution--a Stanley touch that would become sublimely refined by the 1950s. While it's not exactly The Birds, the avian threat in "Brings Some Friends..." is a mite unsettling.

Our last piece today, "The Haunted House," introduces a major Stanley theme: the supernatural. Stanley dabbled in the genre in a 1945 "Oswald the Rabbit" story, but it is more fairy-tale than spook-show. Here, John Stanley introduces supernatural elements into everyday settings. It's open to interpretation, as in his masterpiece, "The Guest in the Ghost Hotel," in that the ghostly goings-on may, or may not, just be products of over-active child imagination.

Equally important, in "The Haunted House," is the presence of a threatening, physically aggressive adult figure. Kebel is the first of many such figures in the world of John Stanley. Typically, Kebel's entrance is heralded by a fearful discussion of the threat he poses:

While Kebel is just a bad-tempered loud-mouth, his hostile personality is clearly a long-standing thorn in the ephemeral sides of Timmy and Gertie, child-ghosts who mirror Lulu and Tubby in girth and interests. Tubby is comfortable in Timmy's presence, and babbles banalities, including the sublime statement "I play third base good." Lulu and Gertie also find immediate points of connection.

Does any of this really happen, or is it just imaginative wish-fulfillment for Lulu and Tubby? Regardless, a-hole Kebel soon appears to disrupt this peaceful meeting. Unlike the flesh-and-blood "Ol' Mister Grump" of the terrifying "Tubby" story "Hide And Seek" (Little Lulu 79), Kebel shows no signs of being physically abusive. As the kid-ghosts are able to neatly hang up Lulu's and Tubby's hats on a hat-rack, it's possible that the older Kebel is capable of causing harm to our two human protagonists.

Kebel never gets a chance to warm up. Lulu is able to out-shriek him and drive him out of "Carson's ol' house"--perhaps for good. The story's open ending invites a sequel that never quite happened, although the Lulu cast would continue to haunt haunted houses for the rest of Stanley's tenure.

"The Haunted House"'s first page is beautifully written. As the kids approach the Carson house, Tubby proudly traces his personal growth, via the height of its windows that he has broken. This says much about Tubby's personality--and offers us this information without awkward exposition.

The story's final frame offers a lovely early example of a Stanley off-beat finale. Any other author would have been satisfied with the soothing farewell uttered by Lulu. Not Stanley; he focuses on Tubby, already lost in his personal myopia.

These Little Lulu one-shots were obviously a success. Three issues were published in six months' time, and within 10 successive numbers of this peculiar try-out series.

It may not have yet been clear to John Stanley, in 1946, that Lulu would soon eclipse all his other comic book work. With each issue outdoing its predecessor in narrative and comedic flair, the popular success of Stanley's Little Lulu was a rewarding response.

Monday, August 29, 2011

Saturday, August 13, 2011

"B-Be Careful of the Doll:" Three Stories from Little Lulu Four-Color 110, 1946--story and art by John Stanley

We haven't had any Little Lulu material in awhile. Stanley Stories readers really like seeing the early stories in color. These stories were created with color in mind. The hues that fill the shapes really complete the pages.

In thanks for your kind indulgence, as I step down from my New Funnies fixation, here's another installment of the John Stanley-drawn Little Lulu.

This was Stanley's third Lulu one-shot, with a publication date of April, 1946. In these stories, created in late 1945/early '46, Stanley feels more at home with the characters and the turf. He begins to deviate from the Marge Buell formula--and to take chances with his stories.

Today's three selections range from an unsung gem of status-shifting and gender games ("He Can't Hurt Us") to elaborate screwball comedy ("Stuff An' Nonsense") to one of Stanley's earliest pantomime pieces ("Working Girl").

"He Can't Hurt Us" takes the battleground of childhood seriously, to best engage its readers, and then turns it on its ear. It is one of Stanley's first gender-reversal comedies. Tubby is a timid, lazy male, capable of self-defense, but too easily distracted by passing whims.

Lulu steps into a father/big brother role, in an attempt to "man up" Tubby. Her efforts to teach Tub boxing are in vain. Tub resorts to a different type of "boxing" to settle his beef with Willy. I wonder if this visual pun was intentional?

Tubby is not yet the divinely self-deluded Quixote of the 1950s. He seems less smart than his later self. Lulu's inherent superiority is under-stated and quite matter-of-fact. She is far wiser in the ways of the world than either of the two males she encounters.

"He Can't Hurt Us" is less developed and focused than Stanley's best gender-war pieces of the '50s ("Five Little Babies," et al), but, as the first of its kind, it's noteworthy.

Lulu suddenly seems younger and less savvy in "Stuff An' Nonsense." This early in the game, Stanley could revise the cast of characters to suit his narrative needs. Lulu's behavior in this story would be unthinkable by the end of the "Four Color" trial run.

"Stuff an' Nonsense" is more akin to Stanley's knockabout comic narratives for the Walter Lantz characters in New Funnies. In the Lulu-verse, Stanley is able to add a layer of comedic status-shifting--the embarrassment of proper adults at the free-form actions of a child.

This 1946 Lulu is still more like the Marge original than the wise, level-headed Voice of Wisdom Stanley's version would soon become. She's very much a naive little kid, and she follows the logic of the world as she understands it, based on what little she knows.

Her intentions are sincere and thoughtful; she wants to get her mother something special for her birthday. Lulu is not set on mischief, as she is in the Marge cartoon panels, on in the earlier issues of Stanley's Lulu. Her innocence and Tubby-like stubbornness to stay on task makes her an unconscious agent of chaos.

The idea of bringing a horse into a suburban household is right out of an Irene Dunne screwball comedy movie. Stanley is aware of the inherent humor, but he furthers the impact by contrasting Lulu's sober determination with the wrinkle it throws in her mother's social life. (She has the priest over, for goodness sakes!)

The three adults suffer shock, embarrassment and physical discomfort from the invasion of Edgar, the decrepit horse, into their civilized daily doings. Like Tubby, in "He Can't Hurt Us," Lulu is literally boxed in at story's finis. She loses her magenta frock and is given a social humiliation (near-nakedness) that she doesn't yet grok. She knows she's in trouble, but also that she's too young to really get reamed for her misbehavior.

Typical of Stanley's earlier Lulu stories, "Stuff an' Nonsense" ends on a note of self-awareness. Lulu may seem an innocent, but she knows how to work the system, based on the limited power she has as a kid. Stanley would hone this power-struggle to perfection in his early 1950s Little Lulu stories.

"The Working Girl," as said, is told without dialogue. It is fast-paced, and it invites the reader to consume it quickly. Details are almost diagrammatic, and nothing goes unsaid.

"Working Girl" is a straightforward chain-of-events comedy, told with only a handful of functional words. Stanley had a knack for these silent stories, but there are few full-length pieces such as this in his portfolio. He more often used pantomime for one-page fillers, such as these two, also from this issue:

The last piece makes clever use of page width. It also shows Stanley's trait for ending a story before it really ends. Most other comics creators would have added that last panel, in which the Scottie dog bites the phallus/weiner balloon, and both parties startle at the resultant BANG!

By eliding that obvious finale on the page, we're allowed to let it happen in our heads. This is far more satisfying and makes us readers feel plumb smart.

Stanley's cartooning is far tighter here than in the previous Lulu one-shots. A stronger, more assured pen line gives these stories more visual oomph. He seems not as hidebound by Marge's rotten character designs and breathes genuine life into his cast.

Animals a la Stanley are always a delight. Edgar, the obese, oblivious horse in "Stuff," is particularly funny and nicely cartooned. The sprightly, angular Scottie dog in the one-pager is also spot-on.

The sparse, functional interiors are akin to Charles Schulz's, in the early years of his Peanuts strip. Both artists were producers of slick magazine gag cartooning, and understood that the settings simply needed to be there, and be tidy.

Stanley's urban cityscapes and household interiors are more elaborate than Schulz's. He had larger panels, and longer narratives in Little Lulu. Such details counted for far more here than in the pint-sized newspaper strips of Schulz.

Stanley avoids the flat proscenium view in his panel compositions. There is a constant suggestion of depth and dimension in these simple drawings. Stanley varies his viewpoints, from long shots (to depict a comedic event in detail) to middle shots (best suited for conversational scenes) to effective use of close-ups.

He invests the elemental linework with enough depth to make its recognizable, inhabitable world come alive for the reader. As well, all straight lines are ruled, which gives the settings a solidity. Color, as said, was the final touch. Without it, these stories have a ghastly, under-nourished look.

John Stanley was a thoughtful cartoonist with strong attention to detail. Whether his work is tight (as here) or loose and free (his "Peterkin Pottle" and "Raggedy Ann and Andy" stories), it always has authority and a strong presence.

This would be the last Lulu artwork he would create (save for the title's covers) until 1951. Stanley's duties as writer, on a number of series, made the labor of cartooning Lulu a liability. He had bigger fish to fry (or so he thought) as he strived to create original comics series from 1946-49. Lulu was his inevitable touchstone, and by decade's end, he was resigned to his role as writer of this highly successful comic-book iteration.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)