Have crowd, will please! Though I've just about exhausted the other John Stanley stuff, I still have the early Little Lulus to fall back on. I have bypassed these stories for a few years, as I've dug around in Dell/Western comics history, in search of unexplored Stanley stories.

My admiration for these stories is high. They represent an early plateau in John Stanley's comics career. After two years of sometimes-inspired knockabout comedies for the likes of New Funnies, Animal Comics and Our Gang Comics, Stanley had emerged a solid comedic writer and cartoonist, with a strong command of character, narrative stakes and dialogue.

Marge's Little Lulu was a prestige project--its source was not Hollywood animated cartoons. Low though Marge's comedy may have been, its publication in a national slick magazine gave it higher status than the likes of Andy Panda and Johnny Mole.

Not to knock those 1943-45 efforts! Stanley quickly proved himself the funniest creator on Western Publications' payroll. Carl Barks, on the West Coast, had yet to hone his comedic sense to the heights he would reach at the end of the decade. Walt Kelly and Stanley ran neck-and-neck as celebrators of comedic chaos.

Kelly can be devastatingly funny in these early comic book works. His more leisurely, wordy pace sometimes drowns his '40s comics in an excess of detail. Kelly would peak as a writer alongside Stanley, although in the higher-status world of syndicated newspaper comics.

John Stanley becomes an expansive, thoughtful writer via Little Lulu. Though the series quieted his more antic side, he gained much in terms of character development, escalating narrative stakes and the eternal balance of light and dark.

Missing from the mix is his hand as cartoonist. As of this issue, Stanley surrendered the finished artwork to the team of Charles Hedinger and Irving Tripp. This switch upset character creator Marge Buell, and is a visual low point in the series. Lulu wouldn't look right again until late 1949, when Irv Tripp and others had more or less perfected the look-and-feel of the feature.

Stanley had free rein to vary his story lengths in these Little Lulu one-shots. Though he had written several long narratives for earlier "Four Color" one-offs, many of those stories seem breathless and over-stuffed when compared to his Lulu work. In his short stories for the anthology titles, which had a strictly regimented page count, Stanley the improviser sometimes wrote himself out before a story was over.

Lulu gave him the privilege to make page count serve narrative. If a story needed to be 24 pages, or four, that was fine. This was exactly what he needed to grow as a writer.

In the three selections from this 52-page magazine, we have stories of 16, 5 and 10 pages' length. The stories move at the speed required by their situations.

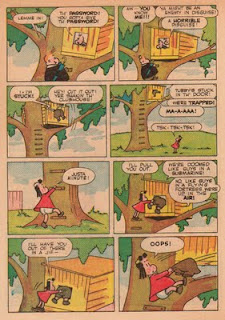

Early occurrences of classic Stanley themes appear in these stories. In the first, and longest, piece, "Fights Back With a Club," Stanley expands upon the gender-war of the previous issue's "He Can't Hurt Us." Added, this time, is the further stakes-raiser of cross-dressing. This introduces a whole new world of humiliation for the eternally proud, stubborn Tubby Tompkins... and brings peace to a war-torn world.

From trouser loss to unconvincing drag, Tubby fights in vain for his masculine dignity. That is, until he discovers that he kinda likes knitting doilies.

This is the first of many instances of cross-dressing by Tubby. A means to an end, this socially awkward action never really bore fruit for the self-deluded Tompkins. Did this stop him from donning dresses and ratty wigs? You already know the answer...

This cheerful act of vulnerability puts a kibosh on the boys v. girls business. In the unusual half-page panel that closes the story, males and females are joined together in productive harmony. While it's an amusing finale, the kids' comfort level in their united efforts is a smart, satisfying wrap-up to a story that bounces all over the comic/narrative map.

The anonymous child's closing comment, "I hope this here thing is washable!," anticipates the attitudes of Charles Schulz's early Peanuts characters. It's no stretch to imagine c.1952 Charlie Brown uttering this concern.

Today's second feature, "Brings Some Friends Home to Dinner," is a follow-up to the prior issue's "Stuff an' Nonsense," with its theme of animals that bring chaos to Lulu's barely-civilized life--and impact the status quo of her long-suffering parents.

The pigeons are antic aggressors in this short story, and they quickly become a threatening (and possibly permanent) element in Lulu's world. The story ends without resolution--a Stanley touch that would become sublimely refined by the 1950s. While it's not exactly The Birds, the avian threat in "Brings Some Friends..." is a mite unsettling.

Our last piece today, "The Haunted House," introduces a major Stanley theme: the supernatural. Stanley dabbled in the genre in a 1945 "Oswald the Rabbit" story, but it is more fairy-tale than spook-show. Here, John Stanley introduces supernatural elements into everyday settings. It's open to interpretation, as in his masterpiece, "The Guest in the Ghost Hotel," in that the ghostly goings-on may, or may not, just be products of over-active child imagination.

Equally important, in "The Haunted House," is the presence of a threatening, physically aggressive adult figure. Kebel is the first of many such figures in the world of John Stanley. Typically, Kebel's entrance is heralded by a fearful discussion of the threat he poses:

While Kebel is just a bad-tempered loud-mouth, his hostile personality is clearly a long-standing thorn in the ephemeral sides of Timmy and Gertie, child-ghosts who mirror Lulu and Tubby in girth and interests. Tubby is comfortable in Timmy's presence, and babbles banalities, including the sublime statement "I play third base good." Lulu and Gertie also find immediate points of connection.

Does any of this really happen, or is it just imaginative wish-fulfillment for Lulu and Tubby? Regardless, a-hole Kebel soon appears to disrupt this peaceful meeting. Unlike the flesh-and-blood "Ol' Mister Grump" of the terrifying "Tubby" story "Hide And Seek" (Little Lulu 79), Kebel shows no signs of being physically abusive. As the kid-ghosts are able to neatly hang up Lulu's and Tubby's hats on a hat-rack, it's possible that the older Kebel is capable of causing harm to our two human protagonists.

Kebel never gets a chance to warm up. Lulu is able to out-shriek him and drive him out of "Carson's ol' house"--perhaps for good. The story's open ending invites a sequel that never quite happened, although the Lulu cast would continue to haunt haunted houses for the rest of Stanley's tenure.

"The Haunted House"'s first page is beautifully written. As the kids approach the Carson house, Tubby proudly traces his personal growth, via the height of its windows that he has broken. This says much about Tubby's personality--and offers us this information without awkward exposition.

The story's final frame offers a lovely early example of a Stanley off-beat finale. Any other author would have been satisfied with the soothing farewell uttered by Lulu. Not Stanley; he focuses on Tubby, already lost in his personal myopia.

These Little Lulu one-shots were obviously a success. Three issues were published in six months' time, and within 10 successive numbers of this peculiar try-out series.

It may not have yet been clear to John Stanley, in 1946, that Lulu would soon eclipse all his other comic book work. With each issue outdoing its predecessor in narrative and comedic flair, the popular success of Stanley's Little Lulu was a rewarding response.

No comments:

Post a Comment